Sorry, but nothing matched your search terms. Please try again with some different keywords.

Sorry, but nothing matched your search terms. Please try again with some different keywords.

“Another week gone and no newsman yet. These months—years perhaps—will to a certain extent be a blank to us. We know nothing of what is going on the states, nothing of the political maneuvers. President’s messages, doings of Congress, elections of senators and assemblymen and the thousand and one maneuvers of the day, riots, mobs, fires, rail-road accidents—in fact I shall be a kind of Rip van Winkle & it will require the first ten years after returning to learn what has taken place while away.”

–Letter from A.W. Genung in Curtissville, San Joaquin District to “Woodward,” Dec 16, 1849, from James W. Milgram’s The Western Mails.

Imagine leaving everything and everyone you know and moving across the country to live in the wilderness, hoping to make your fortune in gold, silver, or copper. Living 1000 miles or more away from home, the only way to talk to your family and friends, and the only way to know what was happening outside your immediate vicinity, was through letters and newspapers: the mail.

Mail, including letters, supplies, and goods, was often freighted in by steamship from San Francisco to the port of Yuma. From there, items either continued up river or were loaded onto wagons, coaches, and pack animals and taken out to towns and camps.

The stage lines and buckboard lines that carried mail and supplies also transported passengers on a regular basis between towns, sometimes requiring at least one overnight stay. These vehicles were extraordinarily uncomfortable, however. After making the much longer overland (cross-country) trip on stagecoach, journalist Waterman L. Ormsby famously said, “I NOW KNOW WHAT HELL IS LIKE. I’VE JUST HAD 24 DAYS OF IT.”

Steamers left San Francisco for the Gulf of California every 20 days and then traveled up the Colorado River. The port at Yuma was a major artery in the delivery of supplies to Arizona.

The steamboats transported not only mail and goods, but also people. In 1874 Martha Summerhayes traveled on the steamboat Gila from Fort Yuma to Fort Mohave. In her book Vanished Arizona, she describes the conditions:

The staterooms “were always stuffy and noisy, and in the summer they were so suffocatingly hot.” In the dining room, “the metal handles of the knives were uncomfortably warm to the touch; and even the wooden arms of the chairs felt as if they were slowly igniting… A siesta was out of the question, as the staterooms were insufferable; and so we dragged out the weary days.”

Entrepreneurs from the Tucson area, such as Pinchney Tully, Estevan Ochoa, Pedro Aguirre, Mariano Samaniego, J.D. Kinnear, and William “Curly” Neal, provided much- needed services between short distances.

Tuffy Peach delivered mail on horseback three times a week between Camp Verde and Payson from 1910-1914. His route was 52 miles long, lasted 11 hours, and required one change of horse. When interviewed by the Arizona Philatelist in 1968, he described his work:

“I often had mail piled so high in front of me that I could hardly see where my horse was treading… “But, gosh, those horses knew the mail route better than the dispatch riders. We couldn’t get lost if we tried. Our horses wouldn’t let us.”

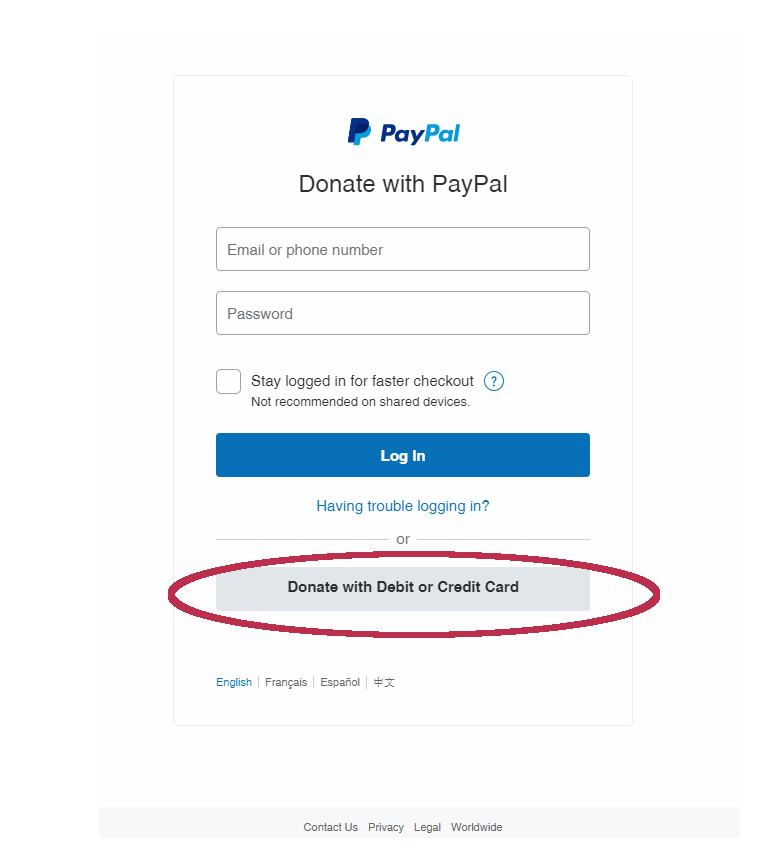

Once you hit the blue button at the bottom of the form, you will be taken to PayPal to complete your gift. YOU DO NOT NEED TO HAVE NOR USE A PAYPAL ACCOUNT. Please click on the “Donate with debit or credit card” button near the bottom of the next screen. (See image to right and click on it for an enlargement.)

You should also receive a confirmation email from us. If you do not receive an acknowledgement within ten business days, please call us at 520-623-6652.

Thank you so much for your generosity!